I am an artist interested in words, text and language and in particular the migration of knowledge from the printed page to the internet, so I was excited to be included as an artist observer for this year’s Social Data School; particularly so given its focus on social media, online news and data privacy – all themes that I have been starting to explore in my own work. I am fascinated by the way in which knowledge has moved from slow to fast, books to bytes, peer-reviewed to free-for-all, Encyclopedia Britannica to Wikipedia, and how the resulting deluge of news and information has given us more raw material than we could possibly ever process, and yet at the same time this has resulted in less clarity and more anxiety. How can we possibly make sense of the wallpaper of words which has now become the subliminal backdrop to our lives?

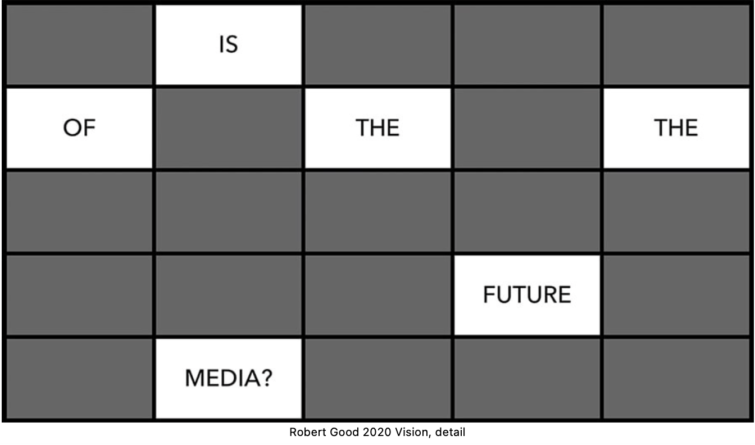

My response has been to use texts from the internet as my source materials: I think of them like tubes of paint to be squeezed out and worked with. I have a background in programming and have taught myself Python in order to automate the data collection process, frequently using the results from Google News and Google searches as my starting points. I then consider how best to re-present these texts in order to consider them and to weigh them, so to speak, and find out their properties, their rhythms, their cadencies and particularities. A digital example of this approach would be 2020 Vision, an animation in which the results of a Google search for ‘What is The Future Of…?’ are fed through a 5×5 array of cells, perhaps suggesting rows of newsroom TV monitors or a bank of CCTV cameras.

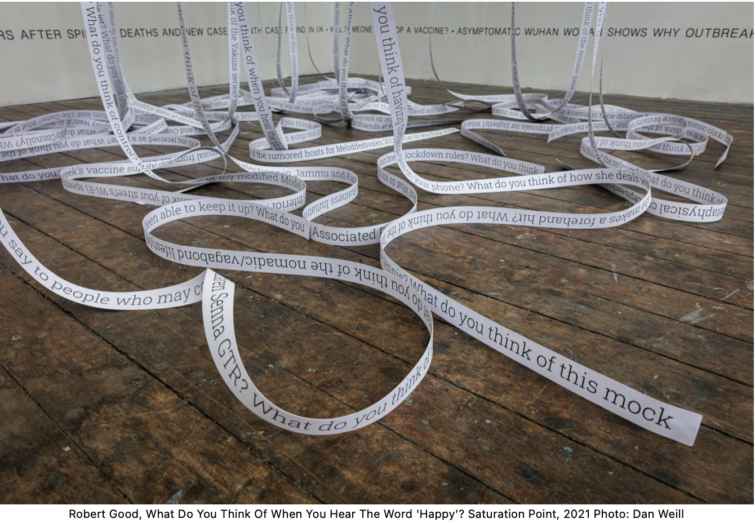

Sometimes it seems best to take the text away from its online environment and into a physical form – for example, in ‘What Do You Think Of When You Hear The Word ‘Happy’? texts flow down from the ceiling, the words frozen in time in a way that allows us to step back and contemplate the torrent.

So I had begun to explore the possibilities for text-based internet art, but, to paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld, I didn’t know what I didn’t know, and I was keen to make connections with others who were exploring similar themes, albeit as academics, researchers, journalists and activists rather than as artists. The Data School seemed like a perfect opportunity – and it didn’t disappoint. Having said that, at first it seemed a shame that we couldn’t meet in person, as I assumed that exchanging ideas with delegates irl must self-evidently be better than via mediated online work spaces, with all their associated problems that we have come to know during lockdown. And yet now I am not so sure. Hosting the Data School online and its international virtual classroom format burst any echo chamber bubbles that might exist, and as a result, the range of experiences, cultural perspectives and approaches to the problems that we discussed was far greater than might have been the case in a conventional format. Holding conversations with delegates from around the world brought to life something of the reality behind the headlines that we read on a daily basis, and this enabled a much more direct appreciation and understanding of the scale, complexity and range of political factors that underpin many of the issues that we discussed.

So I had begun to explore the possibilities for text-based internet art, but, to paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld, I didn’t know what I didn’t know, and I was keen to make connections with others who were exploring similar themes, albeit as academics, researchers, journalists and activists rather than as artists. The Data School seemed like a perfect opportunity – and it didn’t disappoint. Having said that, at first it seemed a shame that we couldn’t meet in person, as I assumed that exchanging ideas with delegates irl must self-evidently be better than via mediated online work spaces, with all their associated problems that we have come to know during lockdown. And yet now I am not so sure. Hosting the Data School online and its international virtual classroom format burst any echo chamber bubbles that might exist, and as a result, the range of experiences, cultural perspectives and approaches to the problems that we discussed was far greater than might have been the case in a conventional format. Holding conversations with delegates from around the world brought to life something of the reality behind the headlines that we read on a daily basis, and this enabled a much more direct appreciation and understanding of the scale, complexity and range of political factors that underpin many of the issues that we discussed.

Topics covered came under the headings of: Digital Research Design and the Project Lifecycle; Machine Learning and Computer Vision; Visualising ‘Fake News’; Social Network Analysis with Digital data; and Data Protection and Surveillance in a Networked World. We used tools such as OpenRefine, Voyant and Gephi to crunch our data and make sense of it.

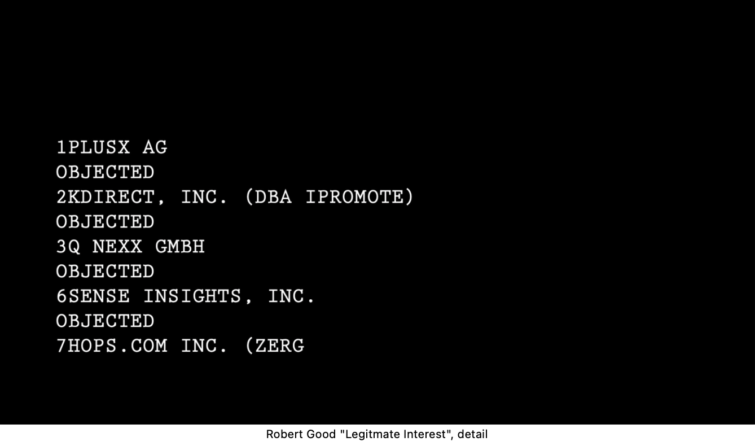

My contribution to the Data School came in the form of a closing presentation comprising some reflections and observations from an art perspective, plus a new digital animation, Legitimate Interest. I found this a particularly intriguing challenge: in the context of academics, journalists, activists and others engaged on the serious business of exposing Fake News, reporting on injustice, proving causal links between social media platforms and their impact on society and lobbying for change, what role can art play? My hope is that art can bring fresh perspectives to the discourse. In this context I created Legitimate Interest, in response to our session on Data Protection and Surveillance in a Networked World. Suddenly I found that my usual mild irritation at the endless pop-up consent forms that appear online had been replaced by a more furious response. Who are these firms wanting to manage my data and claiming legitimate interest in me? Who works for them? What do they do? Down the rabbit hole I went, and returned to create a presentation and an animation based on the consent required to access a single news item on the Cambridgeshire Live website. I hope it has succeeded in articulating something of that frustration.

Looking ahead, I am still processing much of the knowledge that I acquired. Gaggle, Kaggle and many other rabbit holes await further investigation and, I hope, some form of artistic response. In the meantime, a big thanks to Hugo, Anne and the CDH team for including me and to the tutors and my fellow delegates for a challenging and thoroughly enjoyable fortnight.